Russia's New Nuclear Wonder Weapons: The Reality Behind Burevestnik and Poseidon

An analysis of Russia's experimental nuclear weapons and their role in high-stakes diplomacy with the US

On October 26, Chief of the Russian General Staff Valery Gerasimov informed President Vladimir Putin that Russia had successfully tested the experimental Burevestnik missile, a nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed cruise missile. Three days later, Putin announced another successful test of an experimental weapons system, the Poseidon, a nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed torpedo. Putin has since hailed the successful tests as evidence that Russia possesses the world’s most advanced nuclear arsenal.

This situation report examines the details of these recent tests, the controversial development process of both weapons, the operational considerations for their use, and finally, the strategic rationale driving Russia to announce their development now. It concludes that while both the Burevestnik and Poseidon will be the first of their kind when they officially enter service, they will not decisively alter the strategic nuclear balance. Instead, the Kremlin is using the testing as a form of coercive nuclear signaling to deter the US from pursuing unfriendly actions, and convince it to re-engage in arms control agreements that are more advantageous to Russia.

DEVELOPMENT OF RUSSIA’S NEWEST WONDER WEAPONS:

The Burevestnik Nuclear-Powered, Nuclear-Armed Cruise Missile

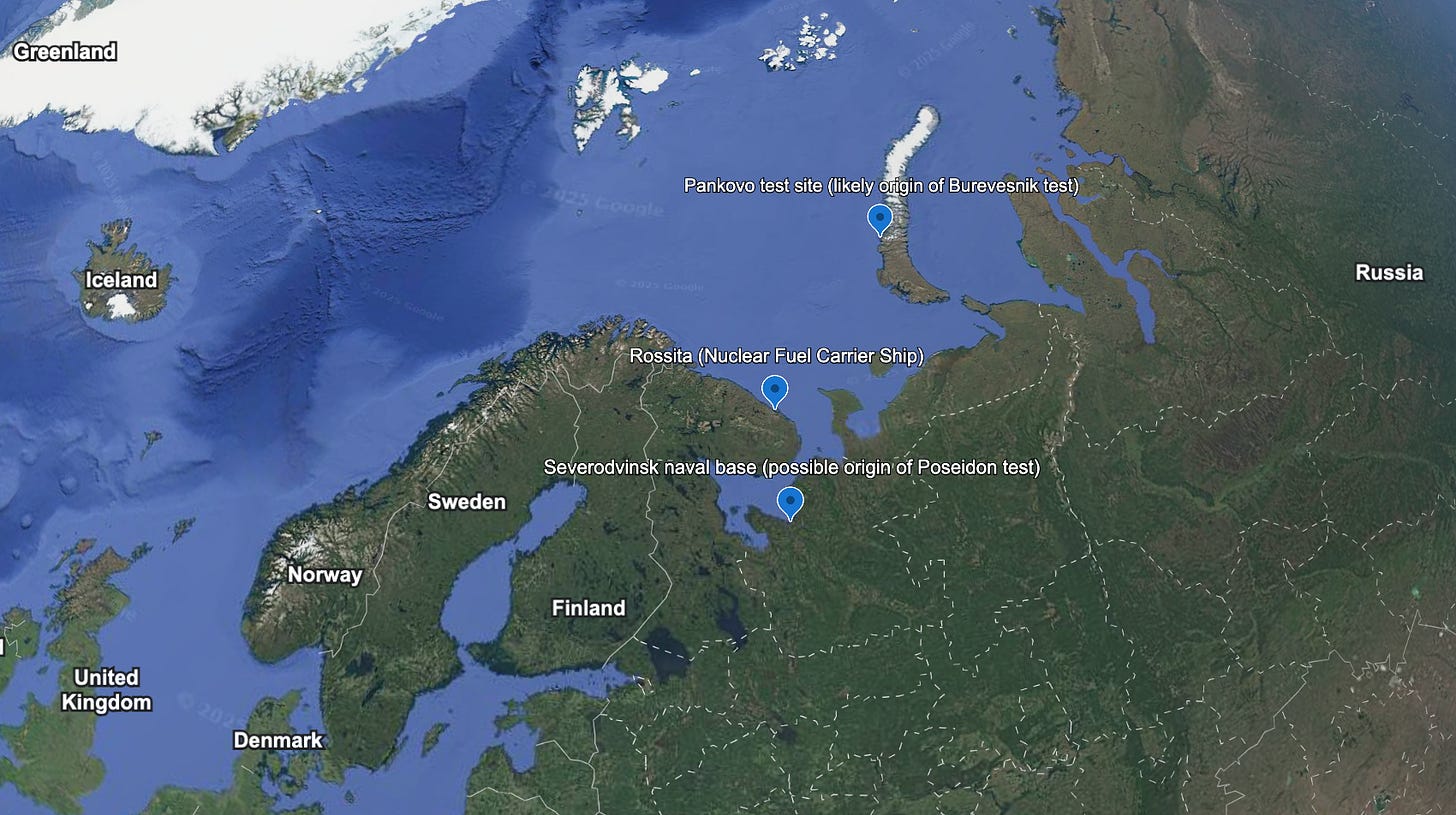

The most recent Burevestnik test is believed to have been conducted at the Pankovo test site in the Russian Arctic peninsula of Novaya Zemlya on October 21.

According to the Russian military, during this test the Burevestnik flew for 15 hours and covered a distance of 14,000 km. This equates to an average flight speed of about 580 miles per hour, approximately that of Russia’s Kalibr cruise missile.

The exact flight path is unclear and likely involved numerous loops through the Russian Arctic to achieve such a long distance. The missile probably came to rest in the Barents Sea, as Rosatom’s special purpose nuclear fuel carrier vessel Rossita was stationed on the Kola Peninsula on the opposite side of the sea from Pankovo at the time of the launch.

Development History:

The idea of a missile powered by nuclear ram-jet engines is not new. The US and Soviet Union both experimented with the concept during the Cold War. Both countries ultimately abandoned development of nuclear-powered missiles as they were deemed too costly and dangerous without clear advantages over alternatives. Advances in technology in the intervening years, particularly in small nuclear reactors and unmanned systems, have likely made the Burevestnik a more feasible weapon system and an attractive addition to Russian strategic forces.

Nevertheless, the Burevestnik has had a long and controversial development. The Russian military has been working on the weapon since at least 2011. Since then, its development has been plagued by years of unsettling failures.

In 2019, the recovery of a damaged Burevestnik prototype from the sea after a test resulted in a radiation leak that killed five Rosatom scientists and two soldiers. An unexplained spike in levels of radioactive iodine-131 and ruthenium-106 in Northern Europe between 2017 and 2018 may also be attributable to Burevestnik testing.

Breakthroughs in the program have also repeatedly been declared. Vladimir Putin previously announced that the Burevestnik completed its “final successful testing” at a meeting of the Valdai Discussion Club on October 5, 2023. Putin may be using this announcement to similarly overstate progress on the weapon’s development.

Operational Considerations:

The Burevestnik is assumed to be an addition to Russia’s second-strike capability. Burevestniks would be launched at the onset of a nuclear exchange but would loiter to conduct follow-on attacks on targets if needed. The theoretically unlimited flight time would provide the Kremlin time to coerce its adversary to stand down or face further attacks.

The yield of warheads the Burevestnik is expected to carry is not yet known.

Russian military experts claim the missile will be compatible with launchers from its Iskander short-range ballistic missile systems and Oreshnik medium-range ballistic missile systems. This compatibility, if confirmed, would carry serious strategic risks. The mixing of conventional and nuclear warheads on shared delivery systems increases the risk that the US or other nuclear-armed adversary might misinterpret Russian military actions in a future confrontation. If Russia’s adversaries mistake a conventional missile launch for a nuclear one, they could launch preemptive strikes against Russian nuclear forces, inadvertently triggering nuclear escalation.

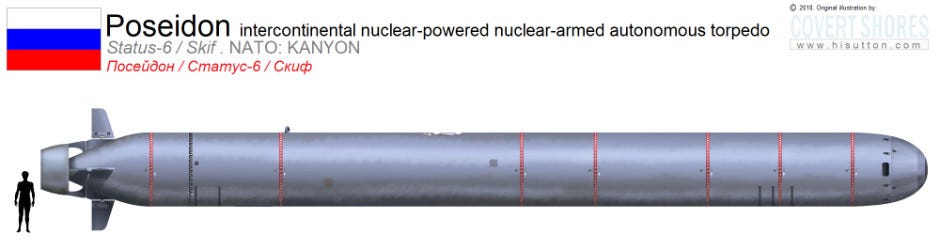

Poseidon Nuclear-Powered, Nuclear-Armed Torpedo

According to Vladimir Putin, the most recent test of the Poseidon was held on October 28. The test involved the launch of the torpedo from a submarine, and the activation of its internal nuclear propulsion system. Unlike with the Burevestnik, Putin did not elaborate on how long the weapon was able to operate.

Putin also did not announce where the testing took place. However, open-source information suggests the White Sea or nearby Barents Sea as the most probable locations for the Poseidon test. The Barents Observer notes that the only two submarines currently capable of deploying the Poseidon, the Belgorod and the Sarov, are both stationed at the Severodvinsk naval base on the White Sea. The Akademik Aleksandrov, a special research vessel identified by naval analyst H.I. Sutton for its previous involvement in Poseidon testing, is also stationed at Severodvinsk. The testing could have also taken place in the eastern Barents Sea, potentially in a specially designated area closer to the prepositioned Rossita Nuclear Fuel Carrier, where retrieval of both the Poseidon and Burevestnik from the seabed would be most feasible.

Development History:

The Poseidon, formerly known as the Status-6, has been in development since at least 2015. Since then it has been involved in a series of test launches from the Sarov submarine. The Poseidon has also been tested as a standalone system capable of launching on its own from the seabed.

The development process for the Poseidon has been less riddled with disaster than the Burevestnik. This is likely because nuclear reactors are already widely used in Russian submarines. Adapting similar technology for a smaller undersea vehicle does not require the same technical leap as achieving sustained nuclear propulsion for an aircraft.

The Pentagon assesses that the Poseidon will be able to carry nuclear warheads with a yield of between 2-100 megatons. The upper limit of this range would exceed the most powerful nuclear devices ever used and could spread radiation across an area as large as 1,700 x 300 km.1

Russian state media has previously claimed Poseidon capable of traveling at exceptionally high speeds, in excess of 200 km/hour (110 knots) through specially designed devices that cause supercavitation. These claims appear to be exaggerated. Pentagon estimates peg the Poseidon’s cruising speed at 55 km/hour (30 knots).

As of 2019, the Kremlin planned the production of 32 total Poseidon torpedoes.

Operational Considerations:

The Poseidon can be launched from specially fitted torpedo tubes, dropped off the back of a specially equipped ship, or deployed independently from a prepositioned staging area deep undersea.

The nominal military purpose of the Poseidon is targeting key US ports and naval bases in the event of war. However, the size of the nuclear payload of the Poseidon, which Vladimir Putin claims “significantly exceeds that of even our most advanced intercontinental missile, the Sarmat,” suggests the weapon is primarily designed to menace countries with the prospect of wanton destruction.

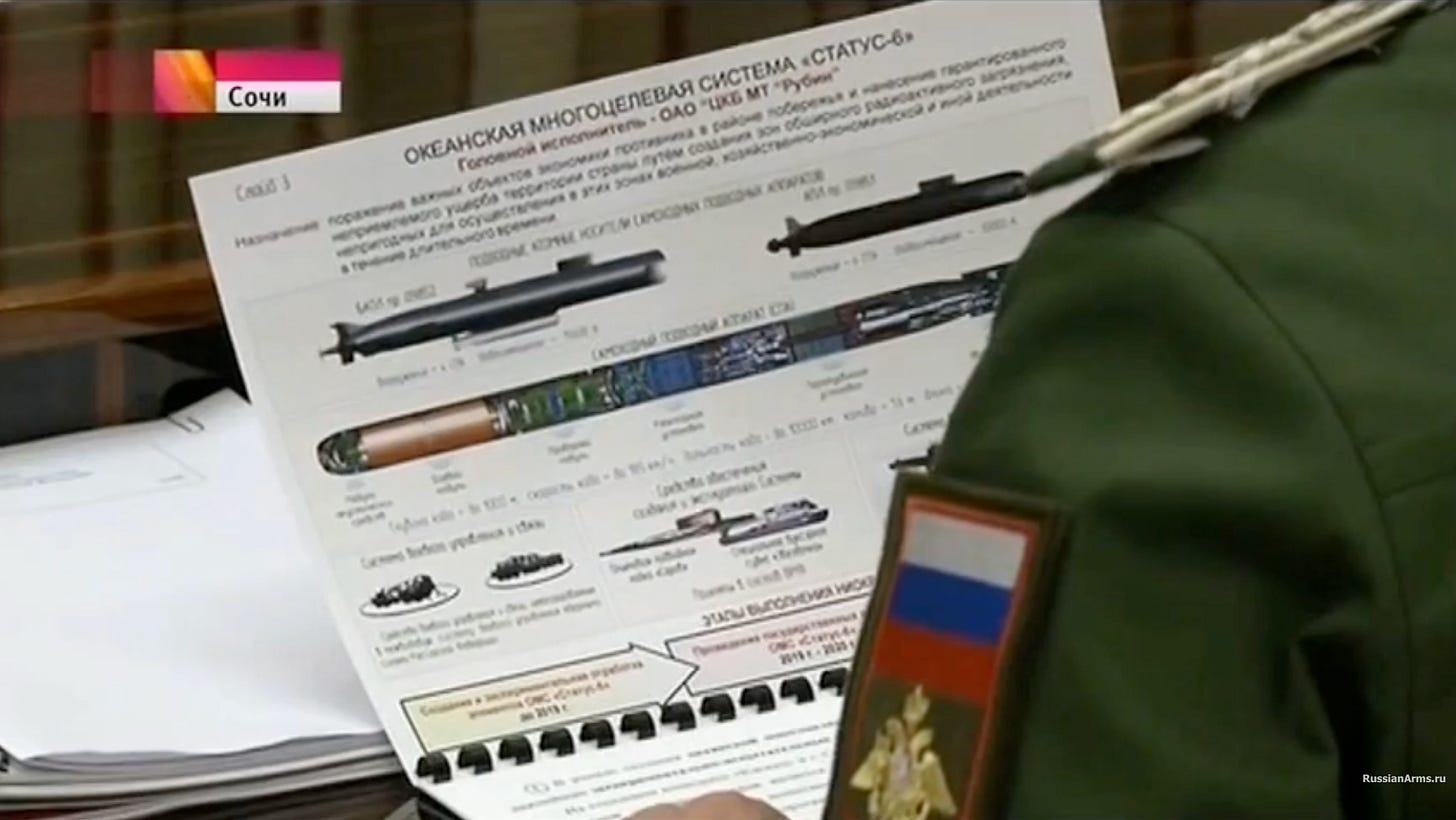

An early draft document on Poseidon, which appeared at a November 11, 2015 meeting between Vladimir Putin and top Russian military officers in Sochi, featured a paragraph summarizing its mission as:

“Damaging the important components of the adversary’s economy in a coastal area and inflicting unacceptable damage to a country’s territory by creating areas of wide radioactive contamination that would be unsuitable for military, economic, or other activity for long periods of time.”2

Nuclear security expert Jeffrey Lewis of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey believes this mission means the Poseidon could be intended for use as a large dirty bomb to spread radiation through waves and water droplets, rendering a country’s coastline and coastal cities uninhabitable.

Former Russian President Dmitri Medvedev, currently Deputy Chairman of the Russian Security Council, endorsed this interpretation in a social media post on October 29, shortly after Putin announced the test, claiming:

“Unlike the Burevestnik, the Poseidon can be considered a doomsday weapon in the full sense of the word.”

Medvedev further emphasized this true purpose of the weapon by insinuating that the Poseidon could make Belgium disappear in a future test.

STRATEGIC RATIONALE:

The actual military value of both weapons, which may still be months or years away from officially entering service, is questionable.

Both weapons are slow moving. The Burevestnik could take many hours to hit targets in either Europe or North America, while the Poseidon could take days to reach targets in North America. These long, slow journeys provide time and opportunities for defenders to locate and intercept them that fast moving intercontinental ballistic missiles and new hypersonic glide vehicles do not.

Foreseeable technological advances will further undermine the effectiveness of both systems. Quantum sensing and improved undersea sensor networks will make the stealthy Poseidon more detectable, while drone interceptors will make the Burevestnik increasingly vulnerable to interdiction by low-cost air defenses.

The true utility of announcing new milestones in the development of these wonder weapons now may lie in their ability to shape the behavior of Russia’s adversaries, particularly US President Donald Trump. The tests provide the Kremlin a means of subtly coercing the US to avoid escalation against Russia at a critical moment in its war in Ukraine, while simultaneously creating leverage to compel Washington to accept limitations on its strategic forces in upcoming arms control talks.

Coercive Signaling

The announcement of the successful Burevestnik and Poseidon tests comes days after the Kremlin completed its annual Grom exercise, drilling the readiness of the ground, air, and sea components of the Russian nuclear forces.

This sequence of events may indicate a pivot in the Kremlin’s nuclear strategy toward the US. Both the Grom exercise and the Burevestnik tests appear to have been planned to coincide with an ultimately canceled meeting between Russian President Vladimir Putin and US President Donald Trump in Budapest. There are additional indications that Burevestnik testing was conducted, or at least planned, immediately prior to the August 15 Anchorage Summit between the two leaders.

The timing of the tests appears to indicate a form of nuclear signaling by the Kremlin toward the US ahead of major diplomatic exchanges. The Kremlin may be using demonstrations of its nuclear forces and tests of experimental nuclear systems like a sword of Damocles to remind US leaders of the danger of pursuing escalatory actions against Russia. This subtler form of pressure may mark a shift away from the overt saber-rattling that characterized Russian nuclear signaling since the beginning of the war. The change likely stems from President Trump’s decision to adjust the posture of US nuclear submarines in response to former Russian President Dmitri Medvedev’s casual use of nuclear threats in July. This more indirect approach may prove more effective against a US leader who thrives on public confrontation.

The timing of the announcement of the successful Burevestnik test appears to be deliberately planned to deter the US from providing Tomahawk missiles to Ukraine. It follows Vladimir Putin’s claim on October 22 that Russia would deliver a “strong, if not overwhelming, response” to attacks on Russia involving American Tomahawk cruise missiles provided to Ukraine. Previous statements by Vladimir Putin suggest the Russian leader sees the Burevestnik as the means of providing an “overwhelming response.” During a speech in 2018, Vladimir Putin favorably compared the Burevestnik to the more limited conventional capabilities of the Tomahawk:

“Russia’s advanced weapons systems are based on the latest, unique achievements of our scientists, designers, and engineers. One of these is the creation of a compact, ultra-powerful nuclear power plant, housed within the body of a cruise missile like our latest air-launched Kh-101 or the American Tomahawk, yet offering a range tens of times greater—tens of times greater!—and virtually unlimited. A low-flying, stealthy cruise missile carrying a nuclear warhead, with a virtually unlimited range, an unpredictable flight path, and the ability to bypass interception barriers, is invulnerable to all existing and future missile defense and air defense systems. I will repeat these words many times today.”

Leverage in Arms Control Negotiations

The greatest utility of the Burevestnik and Poseidon may be in their use as bargaining chips in negotiations with the US.

The Kremlin has begun signaling to the White House that it wants to reengage in arms control talks. Despite its own repeated violations of arms control agreements such as the Intermediate-Range Forces (INF) Treaty, this desire to pursue arms limitation may be sincere. The Kremlin likely wants to avoid an expensive arms race that would strain Russia’s already weakened economy and allow it to focus on reconstituting its conventional forces after the war.

By amplifying the unique capabilities of the Burevestnik and Poseidon, the Kremlin may hope to generate leverage it can use to convince the US to impose limits on the development of strategic systems the Kremlin fears, such as the Golden Dome anti-ballistic missile system.

Russian Foreign Ministry’s Deputy Director for Non-Proliferation and Arms Control Konstantin Vorontsov made the connection between the two issues during an October 27 meeting of the UN General Assembly. Vorontsov defended the test of the Burevestnik missile before pivoting to an indictment of the US’s Golden Dome project and suggesting the US return to arms control discussions with Russia.

Two weeks earlier, at a press conference in Tajikistan on October 10, Vladimir Putin similarly hinted at Russia’s intent to use the development of new strategic weapons as a means of pushing the US to agree to reciprocate Russia’s unilateral extension of the New START Treaty while a new comprehensive arms control agreement could be reached.

“We maintain contacts through the Foreign Ministry and the Department of State. Will these few months be enough to reach a decision on extension? I believe it will suffice if there is goodwill to prolong these agreements. Should the American side deem this unnecessary, it is totally not critical for us – everything in this regard is proceeding according to plan.

“I have spoken about this before, and it is no secret: the novelty of our nuclear deterrent systems surpasses that of any other nuclear state, and we are advancing this very actively. What I mentioned in previous years is all being developed. We are refining these systems, and I believe we will soon be able to announce new weapons that were previously unveiled. They are materializing and undergoing successful tests.”

The Kremlin may be using the tests of the Burevestnik and Poseidon to demonstrate to the US that the Russian military has nuclear weapons that render the Golden Dome obsolete and that arms control is the only solution to achieve a stable strategic balance. This would overstate the actual impact of these weapons on the strategic balance, as the most consequential nuclear weapons are likely to remain fast-moving intercontinental ballistic missiles—the types of weapons the Golden Dome is being designed to defend against. The intent of this ruse would ultimately be to get the US to unilaterally agree to restrictions on the Golden Dome in exchange for constraints on the deployment of Russia’s new experimental nuclear-powered strategic weapons.